Heat Stress

6 min read

Heat stress in cows happens when they can't dissipate the heat they generate, leading to discomfort and lower milk yields. Unlike humans, cows can start feeling heat stress at temperatures above 20°C. You might notice that your cows breathe faster, graze less, drink more, and move slower in warm weather. Providing shade and ample drinking water is the first line of defence against heat stress. You can also make strategic changes to their management and feeding routine. The podcast included here provides scientific explanations and in-depth strategies for managing heat stress.

Heat stress occurs when cows have more heat than they can get rid of and leads to discomfort and lower milk production. All areas of New Zealand get hot enough to cause heat stress during summer.

We all have an ideal temperature range within which we feel comfortable and our immune system and organs function properly. The comfortable temperature range for a cow is 4-20°C, lower than for a human of 16-24°C.

That’s because cows generate enormous amounts of energy digesting food and producing milk. This is handy during winter but a challenge during summer, when cows absorb more heat from the environment and it’s harder for them to maintain an ideal body temperature.

One way cows get rid of excess heat is by evaporation through their breath and sweat. To increase evaporation, they breathe faster and sweat more, although their ability to sweat is limited. When this isn’t enough, they eat less to reduce the production of heat in their rumen, so their milk yield declines.

High humidity, little cloud cover, and low air movement increase the risk of heat stress as evaporation is less effective, making it hard for the cow to lose heat by sweating and panting.

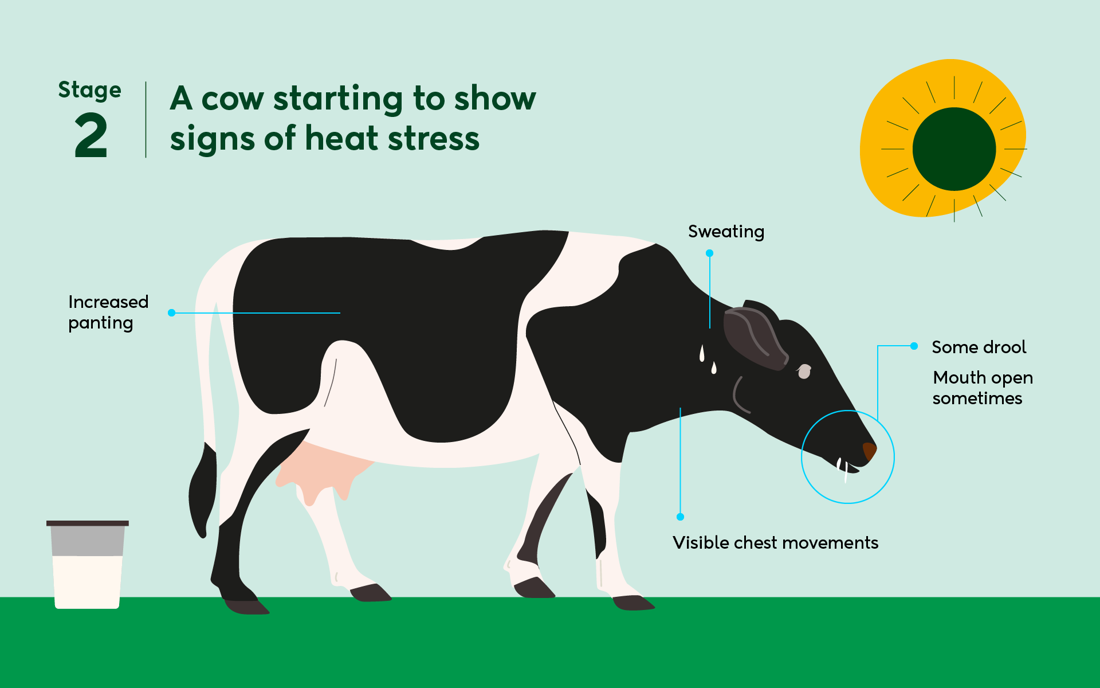

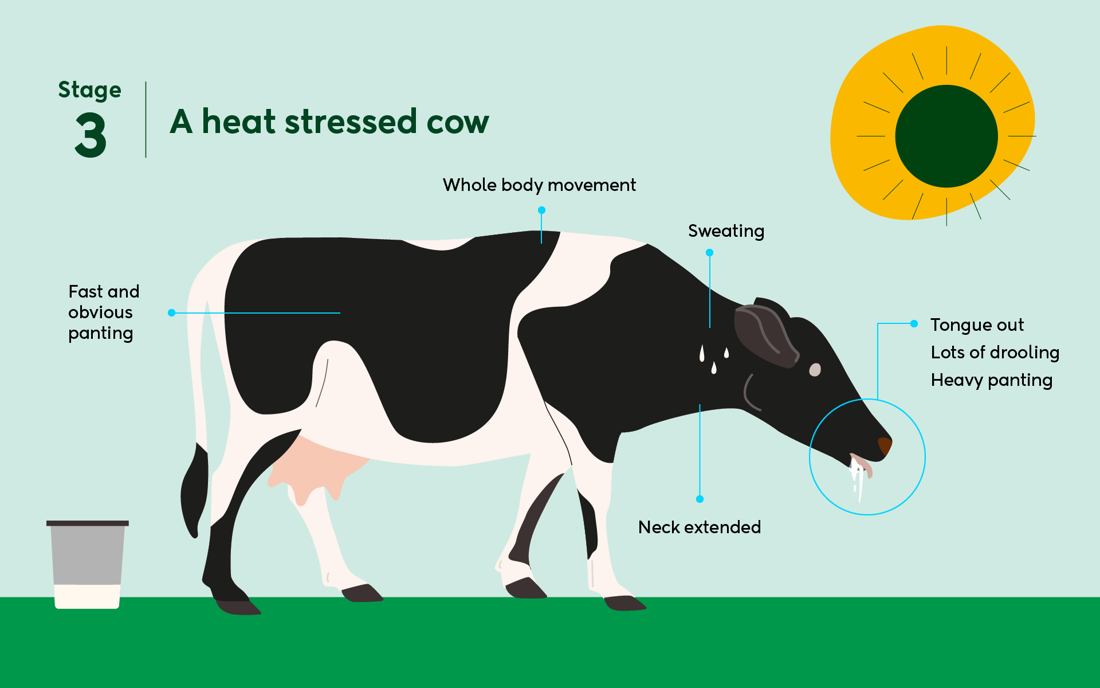

Watch for these five signs:

The earliest indicator of heat stress is increased breathing rate. Check breathing rate by observing a number of cows on a warm summer afternoon – a high producing black cow will be most at risk. More than seven breaths in ten seconds means a cow is not comfortable and is an indication that the herd need cooling.

Dairying regions in New Zealand often experience days when the temperature exceeds a cow’s optimal range for comfort and productivity. Environmental factors such as solar radiation and wind speed can further influence a cow’s heat load.

On a hot day, when a cow starts breathing faster and their breaths exceeds 55 beats per minute, it’s a sign of heat stress. The cow is trying to cool down by increasing her breathing rate. How much stress she experiences depends on the weather conditions and the strategies in place to manage the heat.

To help predict conditions that pose a risk of heat stress, New Zealand has developed the Grazing Heat Load Index. This index includes ambient temperature, solar radiation, and wind speed to assess the thermal load on outdoor cows. When the Grazing Heat Load Index exceeds 55, cows are at risk of heat stress unless they have access to shade or cooling.

Average number of days a year that dairy cows are at risk of heat stress across New Zealand.

Data presented is based on the temperature, humidity, solar radiation and wind speed captured in the Grazing Heat Load Index (GHLI). This index records heat stress above GHLI value of 55. The information was collected during 2006 to 2024 (Woodward, et al., 2024). Colour scale represents the numbers of days that cows are at risk of heat stress. Purple lines depict local regional councils.

Modelling indicates that cows are at risk of heat stress annually for 40 to 85 days in New Zealand and this is expected to increase in the future. The number of heat stress risk days annually differs by region, for example, Waikato 69 days, Bay of Plenty 69 days and Canterbury 80 days. The regions with the lowest number of heat stress risk days are Taranaki 38 days, Manawatu 47 days and Otago-Southland 37 days.

But heat stress is not just a challenge for warmer regions. By 2050, the number of heat stress risk days is predicted to rise even in regions previously less prone to such conditions.

Identifying or predicting regional herd-level heat stress in dairy cows can inform day-to-day operational decisions and long-term strategic management decisions.

To minimise impacts on productivity and protect cow comfort, consider the following:

Cows are highly motivated to seek shade when it is sunny, hot, and with little wind, specifically when:

Solar radiation is a measure of how much sunlight is hitting a surface in a specific time and space. It is measured in megajoule per square metre, per day. 2 MJ/m2/h might feel like standing outside on a sunny day, around noon, with no shade; the sun would feel strong on your skin, and you would feel warm quickly.

Cows use shade when there is as little as 1 m2/cow available, it’s recommended to have up to 5 m2/cow available for access by the entire herd to minimise competition.

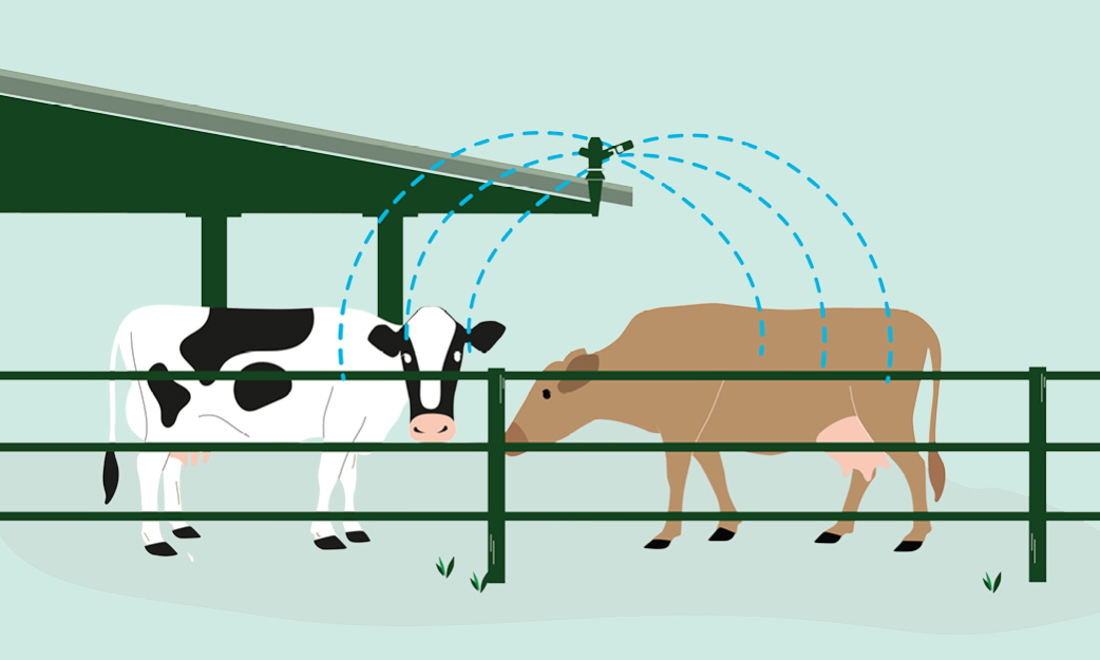

Sprinklers can improve evaporative cooling for 2-6 hours after wetting.

Note: Sprinklers are not effective unless they thoroughly wet the coat, as this only increases humidity, making heat stress conditions worse.

For technical specifications on sprinkler system design, visit the DairyAustralia website.

Using sprinklers can keep cows cooler for 2-6 hours.

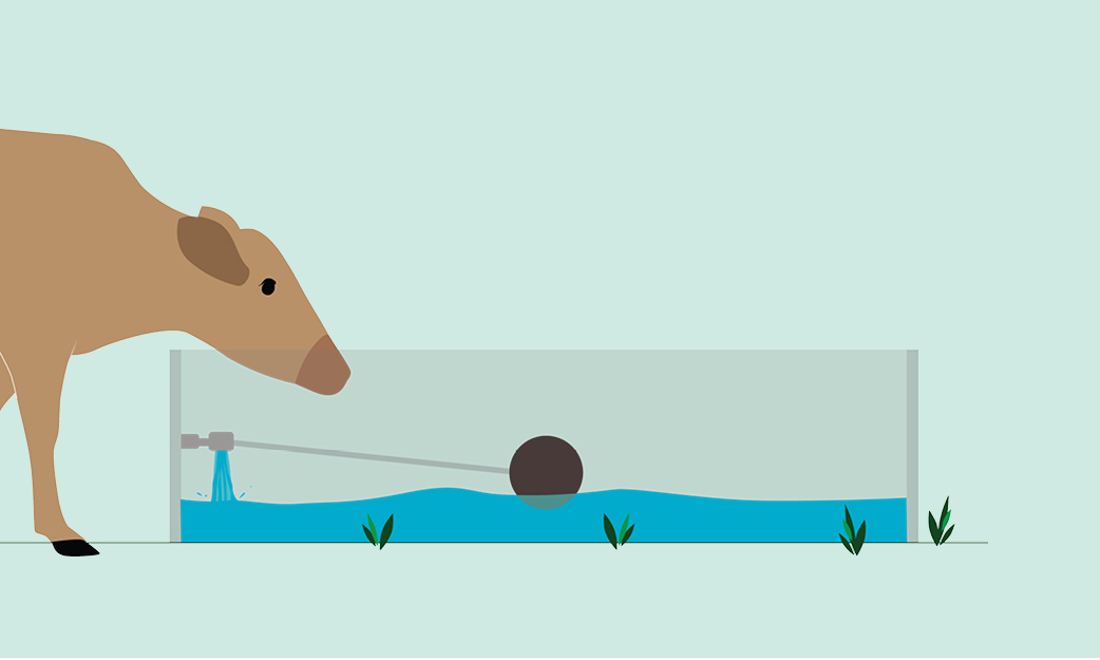

Lactating cows typically require more than 100 litres/cow/day in summer and drink between two to six times per day. A cow can drink 20 litres per minute.

Cows walking to milking and standing on unshaded yards during the heat of the day increases risk of heat stress.

Peak heat production in the rumen occurs about three hours after cows eat. The impact of modifying diet is small relative to the impact of providing shade and cooling. However, there are some changes that can help keep your cows cooler:

How does heat stress affect cows, what are some warning signs, and what can you do on farm to make life more comfortable for your cows? In this episode, Tom Buckley, farm manager for Owl Farm in Cambridge, goes into detail about the strategies they use to combat heat stress. Meanwhile, DairyNZ’s Jac McGowan talks about the science behind heat stress: how it affects cows, the warning signs, and what research is underway.

Now’s the perfect time to check in, plan, and set up for a strong season. We’ve pulled together smart tips and tools to help you stay ahead all winter long.

Whether you prefer to read, listen, or download handy guides, we’ve got you covered with trusted tools to support your journey every step of the way.