Winter pasture management

6 min read

Winter management involves preparing pastures for spring growth and safeguarding them from pugging damage caused by wet conditions. The focus is on achieving target average pasture cover (APC) for calving and meeting milking herd feed requirements. To improve persistence, grazing at the 3-leaf stage is recommended, with the possibility of grazing as low as 2.5 cm due to higher stubble energy reserves in winter. Strategies to prevent pugging damage include building pasture cover before wet periods, early grazing of vulnerable paddocks, and utilising on-off grazing with well-designed stand-off areas. The concept of "sacrifice paddocks" is introduced, allowing a small area of pasture to be sacrificed to enhance regrowth in other areas.

Winter management is about setting pasture up for spring and protecting pastures from pugging.

Winter offers an opportunity to reset the residuals' level for the coming season and ensure leaf growth is promoted in the base of the sward.

Grazing management during winter is about transferring autumn and winter grown pasture into early spring to achieve target average pasture cover (APC) at calving and meet the feed requirements of the milking herd.

This is achieved by lengthening the rotation in late autumn and winter, beyond the time taken to grow three new leaves.

Moist, cool conditions mean tiller death is low. Ryegrass is forgiving of stress, such as severe grazing, except where high soil moisture leads to pugging damage.

Good management to improve persistence involves:

Poor management that will reduce persistence includes:

It is important to determine the leaf stage of your own pastures. Leaf appearance rates mainly depend on temperature and water availability with leaves taking longer to appear in colder temperatures or where water is limited.

The following table shows the approximate leaf appearance rates for different regions in autumn; this can be used as a guide to determine rotation length.

Minimum rotation length (e.g. two leaf stage): Time taken for one leaf to fully grow x 2Maximum rotation length: Time taken for one leaf to grow x3

To determine the leaf stage of your own pasture, collect 10 tillers and compare the leaf stages with the grazing pocket guide pages 10 & 11.

Winter guideline to regional leaf appearance rates based on average monthly temperatures

| Region | Average winter temperature |

Time taken for one leaf to fully grow |

| Northland | 10-13°C | 11-15 days |

| North Waikato | 9-12°C | 12-16 days |

| South Waikato | 7-10°C | 15-21 days |

| Bay of Plenty | 7-12°C | 12-21 days |

| Taranaki | 8-10°C | 15-18 days |

| Lower North Island | 8-10°C | 15-18 days |

| Top of South/West Coast | 7-9°C | 16-21 days |

| Canterbury/North Otago | 2-8°C | 18-72 days |

| Southland/South Otago | 2-8°C | 18-72 day |

Adapted from Julia Lee et al., DNZ Technical Series Issue 3. Assumes that available soil moisture is at minimum 40%, if less than 40% time taken for a leaf to fully grow will increase dramatically. This is a guide actual rate will vary with temperature and water.

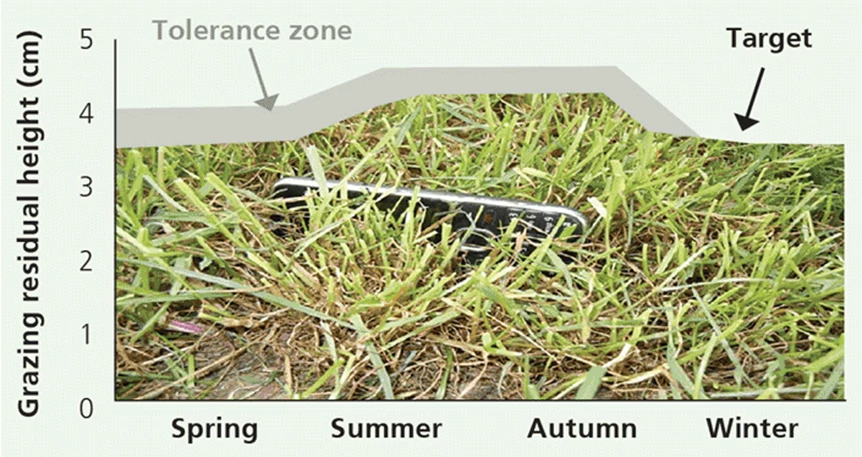

Winter is the time of the year where grazing below seven clicks does not appear to damage ryegrass regrowth. Grazing as low as 2.5 cm or 1200 is possible without reducing pasture regrowth. This is because stubble energy reserves are higher due to slower plant growth and less energy use at night due to the colder temperatures.

Wet weather during the autumn and winter months increases the potential pugging damage to pastures as soils become waterlogged.

Pugging can impact on farm profitability through:

On-off grazing is the most effective grazing strategy for minimising pugging damage. It involves having stock on pasture or crop for short periods of time. For the rest of the time use a well-designed and managed stand-off area.

Shift stock regularly (twice per day) and back fence to reduce excessive treading.

A sacrifice paddock is one way farmers choose to manage their cows and pasture when there are no purpose built stand-off facilities, or where off-farm grazing is not an option.

A sacrifice paddock can take the pressure off the rest of the farm by allowing grass cover to build up while vulnerable soils are wet. The regrowth of a small area of pasture can be sacrificed to enhance the regrowth on the rest of the farm.

Some farmers use a sacrifice paddock when it is dry in autumn. By feeding supplements on a sacrifice paddock it allows future paddocks in the round to build up pasture covers.

The way cows eat (i.e. rate, bite size, chewing time, etc) affects the way nutrients are available and digested in the rumen. Strategically timed pasture restrictions may enable manipulation of nutrients supplied to cows, and change grazing behaviour to enable cows to be fed adequate pasture in short, intensive grazing sessions. This would enable the practice of restricting grazing times to reduce pasture damage and promote pasture re-growth not only to be used in winter for dry cows but also for milking cows particularly in late lactation

Research: To gain a better understanding of cows eating strategies in response to standing-off, the intake and grazing behaviour of dairy cows in early lactation was investigated during the first and main grazing session of the day in a DairyNZ study. Cows were grazed according to three treatments

Results showed daily pasture intake per cow did not differ between the three treatments. Cows in differing treatments managed their time available to eat differently. Cows in the 1x8 group had the highest bite size for the longest time and the steadiest bite rate, meaning they had the highest DM intake, especially in the first few hours. These cows also had the highest rate of hunger hormones, therefore how motivated cows are to eat, is determined by how hungry the cows are.

Impact on Milk Production: The impact on milk production is dependent on the resultant loss in pasture growth if the cows are not stood off, the stage of lactation, the timing of pasture allocation, the walking distance and farm topography and the quality of the standoff facilities.